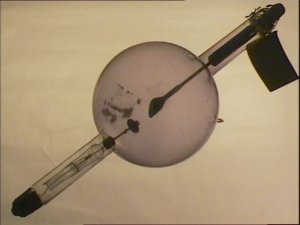

Spherical glass bulb (purple from radiation damage) with cylindrical stems carrying the electrodes (cathode end broken).

The Coolidge Tube, first produced in 1913 by W. Coolidge, is the forerunner of all the types of x-ray tubes in common use today. The Coolidge tube was the first type of practical x-ray tube to employ the principle of thermionic emission.

A tungsten filament is used as the tube cathode, and during operation is heated to incandescence by passing a current through it. This causes the filament to emit electrons at a rate dependent on the temperature of the filament. The electrons are then accelerated towards the tube anode by the strong tube voltage. Upon hitting the anode, the electrons are decelerated very rapidly, and shed their excess kinetic energy mostly as heat, and partly as x-ray radiation. To prevent the electron beam from dispersing due to repulsive forces between the electrons, the cathode filament is surrounded by a metal focusing cup at a high negative potential, that has the effect of converging the beam to a relatively small focal area on the anode. X-ray tubes previous to the Coolidge tube (known as Gas Tubes), relied for their electron source, on the tube voltage being strong enough to 'pull' electrons from the cathode. These were accelerated towards the anode, and collided with residual gas molecules purposefully left in the tube, ionizing the molecules and causing the ejection of more electrons. In this way, the required electron beam was built up with a kind of 'avalanche effect'. However, the number of electrons in a beam produced this way, and their energy upon collision with the anode, were both dependent on the gas pressure within the tube, which was rarely stable, and difficult to control. In addition, the number of electrons produced in this way, was, by today's standards extremely small, and hence the intensity of the produced x-rays very low, leading to very long exposure times.

The Coolidge tube, using as it did thermionic emission to obtain a source of electrons, removed the dependency on residual gas for the number and energy of the electrons in the electron beam (an indeed in Coolidge tubes, almost all gas is removed). In fact, as the number of electrons produced depended on the current applied across the cathode filament, and the energy of the electrons on the tube voltage, the Coolidge tube made it possible to easily and independently vary the number of electrons (and hence the intensity of x-rays produced), and their energy (and hence the frequency of produced x-rays). Also, thermionic emission allowed a much higher bound on the numbers of electrons produced, and hence lead to a drastic reduction in exposure times.

PF